Most of the twenty-first century written, nineteenth century set novels I’ve read, which are centered on the Black experience in the United States, have focused on the horrors of slavery (see for example, my reviews of Sadeqa Johnson’s Yellow Wife, Sue Monk Kidd’s The Invention of Wings, Dolen Perkins-Valdez’s Wench, and Valerie Martin’s Property). Freedom was presented as a goal, a dream, and a destination for the characters in many of these books, with little page space given over to what freedom looked like, or even could look like, for African Americans during and after the Civil War.

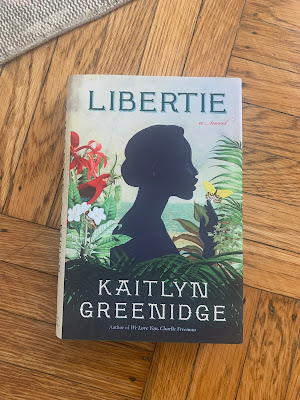

As the title of Kaitlyn Greenidge’s 2021 novel, Libertie, suggests, this is a book all about freedom. Our title character is a freeborn, Black girl in nineteenth-century Brooklyn. As a child, she witnesses her mother’s role in the Underground Railroad, smuggling enslaved people to the North in coffins. And as she grows and matures, Libertie grapples more and more with what freedom means to her. Is true liberty possible in a country so divided along race lines? Could real freedom mean starting over in the Black-led nation of Haiti? And can she shake free of the life her mother, a white-passing, Black, woman doctor, planned for her?

This all sounds very lofty, and the novel does deal with complex history and difficult themes, but at the core of Libertie is this quieter story about the fraught, but loving, relationship between mother and daughter. At times I was frustrated with Libertie’s perspective, especially in her teenage years, but Greenidge’s depictions of the misunderstandings between the protagonist and her mother have a sharply observed psychological realism. Libertie has other important relationships too—with the grieving escapee she sees her mother “raise from the dead” at the book’s opening, with a pair of singing, Black, women college students, who she eventually realizes are romantically linked to each other, and with the Haitian man whom she marries—but it is the mother/daughter bond that makes this a compelling character-driven read.

Those who enjoy the intersection of historical fact and fiction may also want to learn more about the inspiration for the character of Libertie’s mother in the novel—Dr. Susan Smith McKinney-Steward, who was the third Black woman to earn a medical degree in the United States.

Which nineteenth century set novel would you like to see me review next as part of my Neo-Victorian Voices series? Let me know—here, on Facebook, on Instagram, or by tweeting @SVictorianist.

No comments:

Post a Comment