Hello, everyone, and welcome back to my Writers’ Questions series, where I answer aspiring authors’ questions about the writing and publication process. In the last few months, I’ve tackled several marketing related topics, covering areas like publicity, podcasting, and social media. Today I’m back with a post on blog tours, which can also be referred to as virtual book tours.

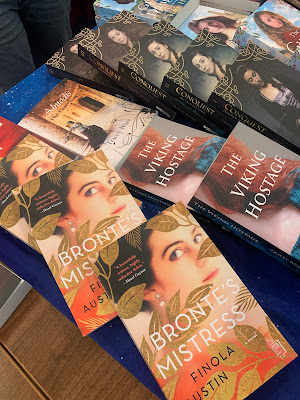

When my debut novel, Bronte’s Mistress, was published in August 2020, my publisher worked with Laurel Ann Nattress to organize a tour (you can check out all the posts here). So, I could think of no one better to help me dive into this topic than Laurel Ann. I hope you enjoy our Q&A, which was conducted via email.

SV: Hello, Laurel Ann, and welcome to the Secret Victorianist! We’ve obviously worked together before, but could you introduce yourself to readers of my blog?

LA: Of course! I’m Laurel Ann Nattress, creator and editor of Austenprose.com, a blog devoted to the oeuvre and influence of my favorite author, Jane Austen. I also run Austenprose PR, a curated online marketing service for authors and publishers. One of the services we specialize in is organizing blog tours or virtual book tours.

SV: So, what is a blog tour? And why might writers want to do one?

LA: A virtual book tour, or a blog tour, is a publicity campaign involving online influencers. The goal is to introduce your book to readers by showcasing it on blogs and social media platforms. The tour has a set timeline, usually one to three weeks, and is scheduled closely before and after the book’s launch date. Each day on the tour includes either a spotlight, excerpt, interview, article, or a review of your book hosted by an influencer. Virtual book tours are a great way to increase exposure, generate reviews, grow your readership, and build your author brand.

SV: How did you get involved in the virtual book tour business?

LA: I am lifelong reader who, on a whim, started Austenprose.com 14 years ago. I reviewed many historical novels for the site and so built great relationships with authors, publishers, and fellow bloggers. I was offered the opportunity to edit Jane Austen Made Me Do It, a short story anthology published by Ballantine Books, in 2011. While promoting my own book, I learned all about the power of online book publicity. In 2014, I decided to turn my knowledge, experience, and connections into Austenprose PR, offering curated online marketing services to authors and publishers to help them connect with their readers.

SV: What is the biggest misconception that authors or publishers have about virtual book tours/blog tours?

LA: Definitely that a blog tour is too much work. I recently had an author tell me she didn’t have “time to go on tour,” but the great thing about virtual vs. real life book tours is that they are much less time consuming and can be entirely tailored to the writer’s and publisher’s needs. If an author wants to write several articles or participate in interviews on blogs to expand their authority, that’s great. But if not, that works too. Many of the tours I curate do not involve author contributions. Instead, they let their book speak for them. Writers that I’ve worked with have found virtual tours to be stress-free during a period when there are many demands being made on their time.

SV: Are there any other big myths out there?

LA: Another one that I’ve heard is that blog tours are “too expensive,” especially for writers who are paying for their own marketing. This doesn’t just mean self-published writers—when I started curating virtual book tours eight years ago, most of my clients were publishers. Gradually that has shifted to include more authors taking the initiative to ensure that their book has an online presence during its launch.

Yes, there are companies out there which boast lists of thousands of influencers, and these can charge you a lot. It always pays to be careful and to do your research by speaking with authors who’ve used their services. But virtual book tours can also be affordable for many. They are typically priced by number of stops and can set you back between $200 and $1,250.

SV: While they’re doing this research, what should writers or publishers be looking out for? What criteria should they use when choosing a company to work with?

LA: Finding the right tour company for your book is key to the success of the tour, and the quality of their influencers is paramount. Below are a few areas to ask questions about to help you find the perfect match.

Genre: Does the tour company handle authors with books in your genre? And do they also pitch to influencers on the perimeter of your genre to expand your readership?

Posts: Do their influencers include a combination of the following with their posts: an introduction, a book description, advance praise quotes, a detailed and honest review, an author bio with online links, an image of the cover, and purchase links?

Sites: How frequently do their influencers publish new posts? Who is their readership, and how many visitors do they receive a year? Do their readers engagement on their site, e.g., with comments and likes?

Social media: Do their influencers have a social media presence, or are they top reviewers on Goodreads or Amazon? Will they be sharing their reviews/posts via social?

SV: I’m going to ask the question that’s probably top of every writer’s mind—do virtual book tours work? As in, do they really help authors sell more books?

LA: Virtual book tours “work” when used in a smart way in conjunction with a marketing and publicity campaign. They are one cog in a wheel that generates engagement, goodwill, and book reviews—the life blood of the publishing business. If no one is talking about your book, recommending it to their friends and followers, or writing reviews, it cannot reach its potential readership.

Adding a virtual book tour to your marketing efforts ensures that your book is featured on prominent book blogs and on social media. With a curated book tour, the odds of reaching your target audience are 100%. Every influencer is hand-picked by the tour director to match your book to the reader/reviewer. This results in a more positive outcome for everyone.

When prospective buyers search online for your title or name, they will find several hits to explore from the tour participants featuring your book. That information is searchable and archived for as long as the blog is online.

Many of the influencers will also cross-post their reviews on retail sites like Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and Goodreads, and share with their followers on social media at no additional cost to you. Publishers love the buzz that blog tours generate, with your book being reviewed and promoted by top influencers every day for several weeks. The exposure builds reader confidence in your book and your author brand, which in turn drives sales.

SV: What’s a big no when it comes to blog tours? Are there any pitfalls writers should avoid?

LA: Blog tours shouldn’t be duplicating content, so book tour companies that send the same article, interview, or an excerpt from your book to all tour participants are doing you a big disservice. First, readers notice it and just move on, leaving a negative impression regarding the book and the author. Second, search engines reward unique content by ranking it higher in keyword search results and send those who repeat content to spam jail by lowering their page ranking. Duplicate content equals search engine disaster.

SV: Thank you so much for all of this, Laurel Ann! Finally, what's an example of a recent virtual book tour you worked on that you think was great and why?

LA: This is a hard question, since I’ve had many great authors and books on tour this year. However, the tour for Bloomsbury Girls, by Natalie Jenner, published by St Martin’s Press in May 2022, was exceptional. This was the second novel that I have worked on with Natalie after her international bestseller, The Jane Austen Society. [Note from SV: check out my review of The Jane Austen Society here!] The tour was a big success. The 75+ influencers were so thrilled to read Bloomsbury Girls and the reviews by a wide variety of historical fiction, women’s fiction, to general fiction readers were amazing. I was so pleased to be able to expand her readership outside the historical fiction genre. It is the greatest challenge to a publicist and takes creativity and persistence. If any of your blog followers haven’t read Bloomsbury Girls yet, I highly recommend it.

Thanks again to Laurel Ann for a great Q&A. Which topics would you like me to cover next as part of my Writers’ Questions series? Let me know—here, on Facebook, on Instagram, or by tweeting @SVictorianist.