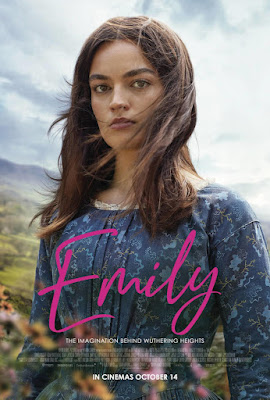

Emily Bronte is the Bronte sibling who’s top of mind for many of us right now, with the release of the biopic Emily (which I’m hoping to see this long weekend!). So, in honor of the most mysterious Bronte sister I thought I’d spend some time on an exercise I haven’t done in a long time on my blog—a close reading of a poem.

I’ve previously shared analyses of other Victorian poems, including Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Pied Beauty,” Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Christmas Bells,” Algernon Charles Swinburne’s “Anactoria,” and Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “The Kraken” and “To Virgil.” Today it’s the turn of Emily Bronte’s “Love and Friendship”.

Here’s the poem…

Love and Friendship

Love is like the wild rose-briar,

Friendship like the holly-tree—

The holly is dark when the rose-briar blooms

But which will bloom most constantly?

The wild rose-briar is sweet in spring,

Its summer blossoms scent the air;

Yet wait till winter comes again

And who will call the wild-briar fair?

Then scorn the silly rose-wreath now

And deck thee with the holly’s sheen,

That when December blights thy brow

He still may leave thy garland green.

Let’s start by paraphrasing the poem in prose to make sure we all understand what Emily Bronte is telling us here.

In the first stanza, Bronte compares romantic love to one plant (“the wild rose-briar”) and platonic friendship to another (“the holly-tree”). Then she poses a question about which “will bloom most constantly,” i.e., be a more consistent source of joy.

In the second stanza she answers her own question, telling us love, unlike friendship, will be short-lived, just as the rose-briar is stripped of its beauty in winter.

Based on this conclusion, in the third stanza she offers some advice: the reader should reject romantic love in the present and invest in their friendships so that in the future (when we’re old) these platonic relationships will bring us happiness.

So that’s what Emily Bronte is saying, but let’s discuss some of the notable things about how she expresses this idea in her poem.

First, I want to draw your attention to Bronte’s use of rhyme. In the first stanza, “tree” and “constantly” rhyme, but “briar” and “blooms” definitely do not, giving us a ABCB rhyme scheme. In the second stanza, again lines 2 and 4 (“air” and “fair”) are a perfect rhyme, while lines 1 and 3 (“spring” and “again”) inch closer to rhyming. Finally, in the third stanza, we get a true ABAB scheme with two pairs of perfect rhymes (“now” with “brow” and “sheen” with “green”). What is the effect of this? The paired rhymes in the last stanza add to the feeling of finality in Emily Bronte’s poem and bring the piece to a more satisfying end. And the progression towards this rhyme scheme we see in the first two stanzas is similar to that of rhetorician building a persuasive argument.

The next detail that’s worth diving into is Bronte’s choice of which plants should represent each subject. Using the rose to depict romantic love is so classic as to border on cliché, but here the decision to make this a “wild rose-briar” adds interest. The choice suggests natural and unbridled passion, reminiscent of the tumultuous love between Cathy and Heathcliff in Bronte’s only novel, Wuthering Heights (1847). Meanwhile, the holly-tree is a plant with a strong association with one time of year—Christmas. This suits Bronte well as her lesson is that we should garland ourselves with friendship now, even though we mightn’t understand its full rewards until later (i.e., at the end of the year/our lives).

Bronte’s message may seem to be a total rejection of romance (after all, she does tell us to “scorn” it), but it is also worth noting that she doesn’t tell us to remove the “silly rose-wreath” from our heads and imagines this crown remaining there, if blighted, on our brow come winter. Maybe then we should read the verse as encouraging us not to take our romantic entanglements too seriously and certainly not to neglect our friendships in favor of them?

One last detail I’d love to point out is the use of alliteration throughout to make the poem pleasing to the ear (“wait,” “winter,” “will,” and “wild-briar” all appear close together, as do “scorn” and “silly,” “blights” and “brow,” and “garland” and “green”). This is a technique that fiction writers can also use in our writing whenever we want to make our prose sing.

Have you seen the new Emily movie yet? I’d love to hear what you think! Let me know—here, on Facebook, on Instagram, or by tweeting @SVictorianist.